When we started our Itasca themed week, we shared the story of how beavers were introduced to Minnesota’s first state park. It is only fitting then that we close our week-long celebration of the establishment of Itasca State Park with another beaver tale.

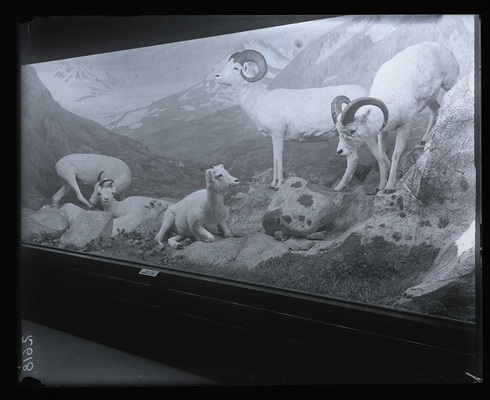

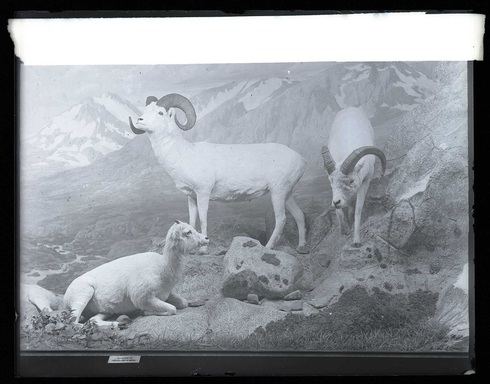

By 1919, the University of Minnesota was the proud owner of three habitat group displays, which were installed in the new Animal Biology building that opened on campus in 1916. In 1911, James Ford Bell, Vice President of the Washburn Crosby company, donated a group of Newfoundland Caribou. An avid outdoorsman, Bell captured the animals himself. He then contracted taxidermist Charles Brandler of the Milwaukee Museum (Milwaukee Public Museum) to prepare and mount the hides, and hired an artist, Charles Abel Corwin of Chicago, to paint a landscape background that the Caribou were installed in front of. The group was moved to the Animal Biology building when it opened, where it was soon joined by a group of White-tailed deer (financed by Bell’s colleague at Washburn Crosby, Frederick G. Atkinson), and Dall’s sheep (Bell) in 1917.

– Museum sheep group from front, 1918, University of Minnesota

– Museum sheep group, central portion, front view, 1918, University of Minnesota

While the deer and sheep exhibits were being installed, Bell and Thomas Sadler Roberts, associate curator of the Zoological Museum, already had plans in the works for more group displays. In a May 17, 1917 letter to Carlos Avery, Commissioner of the State Game & Fish Department, whom Roberts needed permission from in order to collect specimens for scientific collections, Roberts revealed his plan for a beaver exhibit, “Dear Mr. Avery, Your letter of the 6th inst. in regard to getting material for Beaver group was received some days ago. The opportunity seems an excellent one and your offer of assistance is very kind. When is the best time to go?” Roberts went on to explain that he wished to get a “litter of young,” one to mount and place on top of a constructed beaver lodge, and the rest to be arranged accordingly and enclosed within a case.

Roberts further informed Avery that “Mr. Bell, who was to donate the Beaver and bear groups, while he has by no means withdrawn the offer, wishes to wait further development with present… financial situation before going ahead. But Mr. Bell has authorized me to collect the material for the beaver group and prepare to begin the construction of the group… “

With Bell’s financial backing, Roberts hired Charles Abel Corwin, staff artist at the Field Museum in Chicago and one of the first American artists who specialized in painting diorama backgrounds. In addition to his work at the University of Minnesota (he painted four backgrounds from 1911-1919), Corwin was contracted by the California Academy of Sciences and Iowa State University to paint backgrounds for animal habitat displays as well.

With Bell’s financial backing, Roberts hired Charles Abel Corwin, staff artist at the Field Museum in Chicago and one of the first American artists who specialized in painting diorama backgrounds. In addition to his work at the University of Minnesota (he painted four backgrounds from 1911-1919), Corwin was contracted by the California Academy of Sciences and Iowa State University to paint backgrounds for animal habitat displays as well.

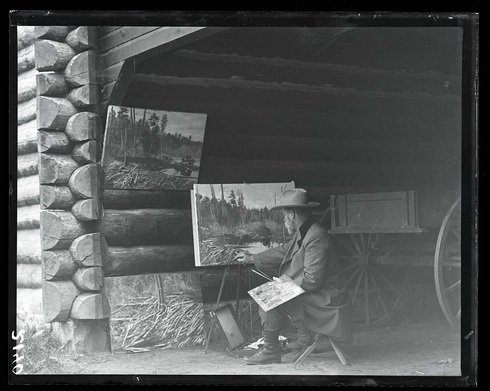

In order to prepare for painting the landscape, Corwin spent two weeks in Itasca State Park at the site of a beaver dam that Roberts personally selected to be the backdrop for the group. Corwin made detailed “sketches” of the site at Seigfried Dam and captured not only the vast landscape, but the detailed structure of the beaver dam itself.

– Mr. Corwin painting, June 1917, Itasca State Park

Letters found in the incoming and outgoing correspondence files in the Bell Museum records highlight Corwin’s stay at the Park and provide detail of not only his work, but that of Roberts and Jenness Richardson, museum taxidermist, as well:

June 12, 1917, Thomas Sadler Roberts to James Ford Bell:

“Mr. Corwin left for Itasca Park Monday a.m. and I expect to leave for same place accompanied by Richardson on Friday (am) or Saturday morning. I have obtained permission from both Mr. Cox and Mr. Avery to collect the beaver and all accessories in the Park… We shall stay at the Forestry School with the approval and introduction of Mr. Cox.”

[William Cox was the State Forester and oversaw the management of Itasca State Park at the time. Carlos Avery, introduced previously, was the State Game & Fish Commissioner.]

June 18, 1917, Charles Corwin, School of Forestry, Lake Itasca to Thomas Sadler Roberts, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis:

“My Dear Doctor: The weather was at first almost impossible but now seems to be settled and beautiful. I found conditions here temporarily unproprietus [sp] except that all are very cordial… we can all get accommodation as to means, there are three cots in the cabin… and they insist that they can take care of all one way or another and will be glad to have you come. Communication by phone has been somewhat demoralized but the stage daily runs each way… they have been very ready and kind in placing me at various points, per power boat to when the beaver are at work. The long dam on Nicollet Creek is long since abandoned and considerable as ancient remains only. Its best down so far studied in on Siegfried Creek just off Lind Saddle Trail down on five miles from Douglas Lodge, but about 1/4 from a landing on the S.W. arm. A number of good houses on lake shore are interesting but not directly available for our use of course… The beaver being long unmolested are probably less shy here then on most places. I watched one patrolling down for half an hour at close range and believe a film might be made with full precaution…”

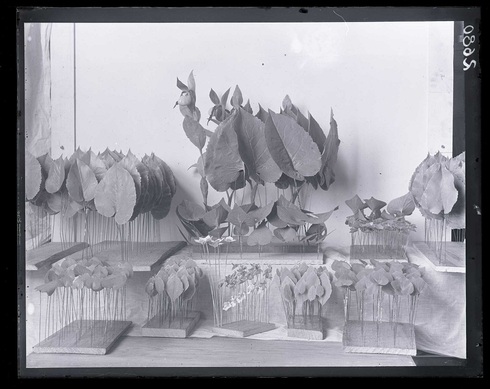

Roberts and Richardson joined Corwin at the Forestry School in Itasca State Park at the end of June 1917 just as Corwin was finishing his sketches. While Roberts and Richardson stayed to collect beaver specimens and “accessories,” to include samples of leaves, flowers, logs, and other botanical material to recreate the physical landscape of the scene, Corwin traveled back to the University to paint the large format background.

Henry F. Nachtrieb, State Zoologist, and head of the Department of Animal Biology, sent a letter to Itasca to update Roberts on Corwin’s progress.

July 7, 1917, Henry F. Nachtrieb, Department of Animal Biology to Thomas Roberts at Itasca State Park:

“Mr. Corwin told me today that he has been instructed to proceed with the background for the beaver group. I got the promise from the Building and Grounds office this morning that a carpenter would be sent over to find out what Corwin wants done immediately. Brandler told me at noon the carpenter did not put in an appearance. Consequently another day or two will be lost next week. Such things are annoying in the extreme, but I suppose a good reason will be given…

…I saw Corwin’s sketches and liked them very much. He seemed very well pleased with them himself. There is one thing to rejoice over.”

Roberts sent the botanical materials that he collected in Itasca back to the University. The secretary in the Department of Animal Biology, Clara Carney, received the materials and sent them to Professor Carl Otto Rosendahl in the Department of Botany for identification. Clara wrote to Roberts to update him on the status of the botanical materials and the progress of Corwin’s work.

July 12, 1917, Clara Carney, University of Minnesota to Thomas Sadler Roberts, Itasca State Park:

“Dear Doctor: The flowers came in fairly good condition. I made the color studies at once and then at night took them to the Botany Dept,. and to Mr. Rosendahl for accurate identification for my own good… That little orchis is a dainty flower. I had never seen the striped coral root before.

Mr. Corwin is hard at it now. The framework to stretch the canvas was put up promptly and he is hanging the canvas today. He made a cute little model group box in which to paint a model background.”

On July 16, 1917, Corwin sent Roberts a letter to update him on his work:

“…The canvas was at once ordered from Marshall Field Co. at Chicago by gram through Mr. Charles at Mr. Bell’s suggestion. It did not arrive till last Wednesday having to come from factory at Boston I believe. Meanwhile thru Dr. Nachtrieb the University carpenters made and put up temporary frame and rings on Monday in the space adjacent to the place selected for the case which you have indicated so that case may be built, or the back of it as soon as you get back if you like and the canvas permanently installed at any time after practical completion. I hung and prepared it by Sat and today laid in the sky. At interim I prepared a model to scale (2″ = 1′) and the tentative background is partly laid in and final composition can be settled upon on your return… in placing the canvas I have used as much of the space as predictable but it can easily be made to fit in less space if I have not made due allowance for the structural requirements of the case: the top ring is now twelve feet from the floor leaving about six inches higher than necessary but you will be better able to judge of these matters at first hand, and in consultation with the joiners…”

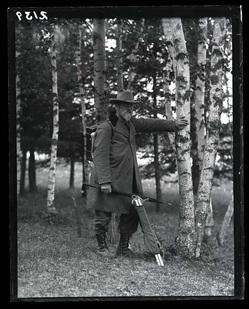

While Corwin was busy painting the background, Roberts and Richardson were busy completing their research and acquiring the needed materials for the construction of the group. Roberts took detailed photographs of the Seigfried Dam site, to include close ups of beaver cuttings and dam infrastructure, as well as wider landscape scenes.

– Beaver cutting, big tree stump, 1917, Seigfried Dam, Itasca State Park

– Beaver cutting, double, July 1917, Deming Lake, Itasca State Park

– Beaver cuttings, partial, September 3, 1917, Itasca State Park

– Beaver lodge at Seigfried Dam, 1917, Seigfried Creek, Itasca State Park

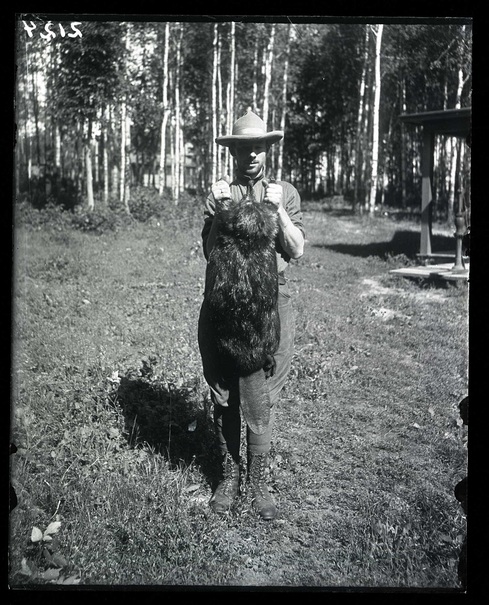

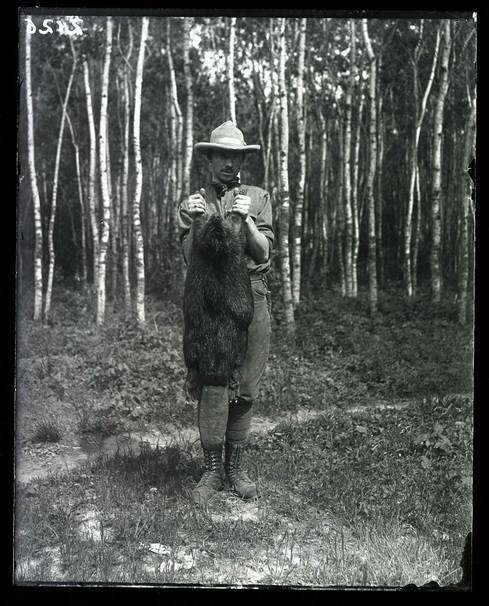

By the end of July 1917, Roberts and Richardson were successful in “collecting” a beaver to skin and mount for the beaver diorama. Roberts photographed Richardson holding the specimen, and also captured him applying plaster to the beaver tail to prepare a mold for use in the sculpted mount he would later prepare.

– Jenness Richardson holding beaver, 1917, Itasca State Park

– Jenness Richardson making a cast of a beaver tail, 1917, Itasca State Park

From the incoming correspondence, we learn that the skin of the beaver, along with another that they collected, were sent off to a New York City taxidermist to be tanned.

August 15, 1917, James L. Clark, Sculptor and Taxidermist, New York City to Thomas Sadler Roberts, Minneapolis:

My dear Dr. Roberts:

I beg to acknowledge the receipt of the beaver skins for tanning and will give them my best attention.

Thanking you for the shipment, I am, Very sincerely yours,

James L. Clark

While the skins were being tanned, Richardson traveled to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, where his father Jenness Richardson, Sr. had been head taxidermist many years prior, to meet with other museum taxidermists to consult on their methods in preparation to sculpt the beaver mount.

August 25, 1917, Jenness Richardson to Thomas Sadler Roberts:

“Dear Doctor: Am returning by way of the Great Lakes and expect to reach Minneapolis in time to start work September first. While in New York I visited the American Museum several times and was surprised to find such a large amount of work being done. Mr. Akeley’s work has stopped as he is now working for the government, but everyone else is busy on group work. I am anxious to get to work on our group as I feel that our group will be much better in the way it is planned, than either the Field or American Museum groups…”

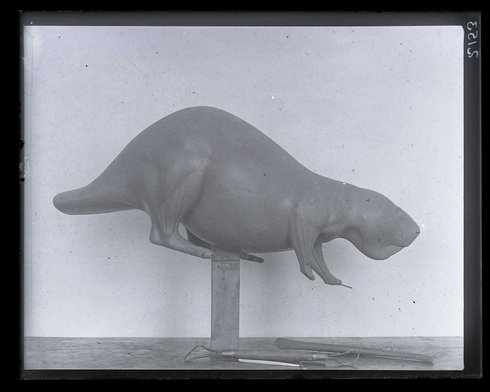

Prior to 1900, taxidermy was an evolving art form. Taxidermists trained at Ward’s Natural History Establishment went on to work at the leading institutions of natural history in the country, where they fine tuned their craft by preparing some of the first true habitat group displays. Carl Akeley, considered the pioneer of modern taxidermy, began at Ward’s in 1883, and later served as taxidermist at the Milwaukee Museum (Milwaukee Public Museum). He also mounted horses for a National Museum of Natural History (Smithsonian) display at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. One of his masterworks, “Four Seasons,” a display of white-tailed deer showing changes in antler growth and coat coloring throughout the year, changed the concept of habitat displays, which up until the turn of the 20th century, were open – they weren’t installed in front of backgrounds and could be viewed from any angle. Akeley’s display included a detailed landscape background, painted by Charles Abel Corwin, and featured extensive foreground vegetation made of wax leaves and grass, which were molded by a casting technique that he invented. “Four Seasons,” purchased by the Field Museum in 1902, was the first large animal habitat group display exhibited at a scientific institution.

Karen Wonders, in her 1993 publication, Habitat Dioramas: Illusions of Wilderness in Museums of Natural History, described Akeley’s revolutionary process:

“From the original manikin he made a plaster mould into which he layered papier mache reinforced with flexible wire cloth. Once dry and released from it’s form, the papier mache cast became a light-weight hollow replica of the original clay manikin. It was on this “second” manikin that the animal skin adhered.”

By 1917, taxidermists at scientific institutions all over the country, to include Jenness Richardson at the University of Minnesota, had adopted Akeley’s methods.

– Beaver, clay model, 1917, University of Minnesota

– Wax work for beaver group, work room studies, August 1918, University of Minnesota

– Yellow Moccasin, wax, made for Beaver group, 1918, University of Minnesota

– Beaver diorama, Bell Museum of Natural History

Construction of the beaver diorama was completed in 1919 when it was installed in a glass case and placed in the Animal Biology building on the third floor. Page 4 and 5 of the May 19, 1919 edition of the Minnesota Alumni Weekly has an article that publicized the diorama: “Call of the Wild.” The article also described the two live captive beavers, also procured in Itasca, that resided in a pool outside of the Animal Biology building in the summer of 1917. For more on these beavers, read the previous beaver posts.

Construction of the beaver diorama was completed in 1919 when it was installed in a glass case and placed in the Animal Biology building on the third floor. Page 4 and 5 of the May 19, 1919 edition of the Minnesota Alumni Weekly has an article that publicized the diorama: “Call of the Wild.” The article also described the two live captive beavers, also procured in Itasca, that resided in a pool outside of the Animal Biology building in the summer of 1917. For more on these beavers, read the previous beaver posts.

What a week! Though it rained in Minneapolis for the past three days, I’ve had sunny memories of Itasca State Park occupying my thoughts as Exploring celebrated the Park’s history. We hope you enjoyed our week-long virtual visit to Itasca through the images from the natural history collections at University Archives. Now it’s time to plan a trip to visit the park in person!