This Wednesday in our series chronicling the adventures of former Bell Museum preparator and director Walter J. Breckenridge, we share just how far – or high – Breckenridge went in order to study birds. In his autobiography, My Life in Natural History, Breckenridge recalled his pursuit to photograph and film with a motion picture camera a family of Great Horned Owls found nesting in Minneapolis in 1931. Was he successful? Read on to find out…

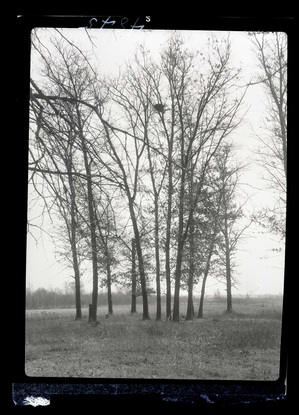

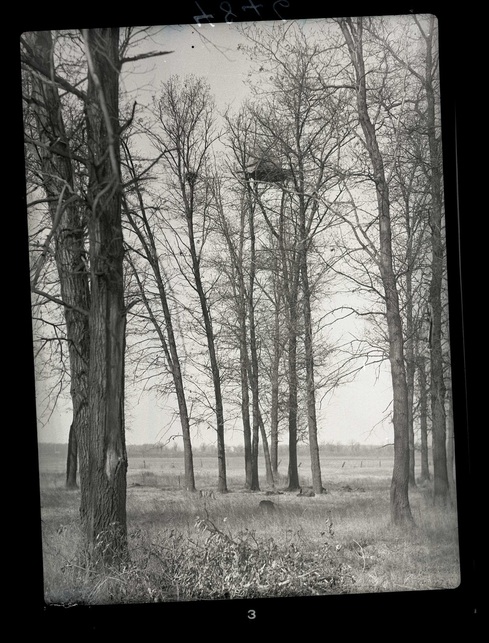

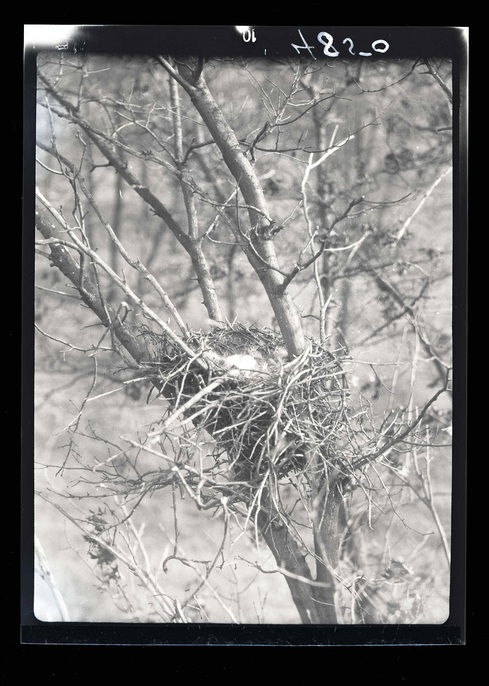

“This nest was high up in an old oak tree, one of several that made up a small grove three or four miles north from my home. After studying the situation, I decided that one of the neighboring oaks was perfectly located to provide a site for a photographic blind about fifteen feet from the nest, which I found contained four eggs. Knowing that great horned owls lay their eggs as early as late February, I calculated that, with an incubation period of 28 days, the eggs probably were well along toward hatching since I found the nest in April. At this late stage of incubation there would be little chance of the bird deserting the nest should I disturb it during my photographic preparations. With this in mind, a friend and I first fastened a trio of heavy poles as a base for my blind at about the level of the nest in the other tree. After a day or two I added some more poles. Then, still later, I bent over some slender poles to form a dome shaped frame. Over this I draped a burlap cover with observations holes… “

– Blind for photographing nest of Great Horned Owl, Minneapolis, 1931

From his blind high above the ground in an adjacent tree, Breckenridge had a prime vantage point from which to photograph the newly hatched owlets and observe the parents feeding the young. Breckenridge recalled:

“The ambitious project was aimed at getting motion pictures of the feeding behavior of the birds. I knew that owls were largely nocturnal and that most of the feeding would occur when the light would be too weak for photography, but I hoped that as the growing young demanded more and more food, at least some feeding would take place when suitable daylight was available.”

– Great Horned Owl nest and eggs, Minneapolis, 1931

Breckenridge returned to the tree daily, climbed to the top to reach the blind, and held out hope that the weather would be in his favor. As he explained in the autobiography, his activities took place during the 1930s “during the Dust Bowl days of the drought.” He explained:

“One of my early morning vigils was interrupted by weather. A strong breeze developed and soon clouds of dust began appearing in the air… Anticipating a still stronger wind from the west, and finding my tree perch beginning to sway dangerously, I beat a hasty descent before my tree, with my added weight, might snap or be uprooted.”

Breckenridge was not deterred by weather nor bird behavior and continued to occupy his blind day after day. He continued:

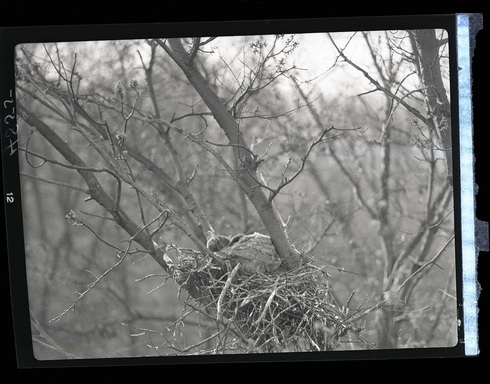

“After several unsuccessful morning watches in my cramped little blind, I finally determined that my disturbing the family routine in the early mornings by climbing to the blind was preventing any feeding of the young until several hours has passed for the normal quiet to be reestablished. With this in mind I determined to take really drastic steps to assure my success. I stuffed my packsack not only with my photographic gear but also with a warm woolen blanket, and ascended to my “flagpole sitting perch” at midnight. I curled up to at least try to sleep through the rest of the night in order to be on hand when morning light brightened enough for photography. I felt confident that if I really did doze off and began shifting about in my sleep, my safety belt would prevent my rolling out of my lofty bedstead. It worked OK and the crack of dawn found me still safely curled up in my tree top hideaway. In the gradually increasing morning light I set up my tripod and camera and awaited the coming of my actors on their precarious stage…

The big question was: Would my actors wait with their acting until the light was bright enough for photography?“

– Great Horned Owls, young, Minneapolis, May 20, 1931

– Great Horned Owls, young, Minneapolis, May 20, 1931.

Though Breckenridge was able to take some still photographs as evidenced by the images above, the light remained too weak for him to record any film of the Great Horned Owls. He recalled, “Always when my [light] meter told me to go ahead and shoot, the owl would fly over to a nearby tree and settle down to roost for the day.” Ever positive, Breckenridge concluded that his efforts were not for nothing, “all the arduous blind building and tedious sitting was by no means lost effort… years later I gave a talk to a local Audubon Society entitled, ‘Movies I Failed to Get.’“