Are you sick of glass plate negatives yet? I certainly do post a lot about them. The fact is I spend the better part of my day looking at the scanned images of the negatives, deciphering the hand-written notations on their envelope enclosures, looking up biological vocabulary and Minnesota locations, and adding corresponding metadata to a master spreadsheet.

To date, more than 5,000 glass plate negatives from the Bell Museum of Natural History collection have been scanned by Digital Library Services. After the images are scanned, the resulting digital files are quality checked, stored, and a set of reference images (at lower resolutions than the original scans) are burned onto a disc so that I can review them to enter the corresponding metadata.

If you have been following the blog, you probably understand why I feel as if it’s Christmas morning each time I get a disc that includes a fresh set of reference images, as by now you have a good sense of the subject matter – the beautiful birds, fury animals, breathtaking landscapes, and outstanding geological features of Minnesota. So imagine my surprise when after I received the latest disc, I waited for it to load onto my computer, cracked my knuckles in preparation for a hearty data entry session, clicked on the first reference file on the list, and was greeted by… TERMITES.

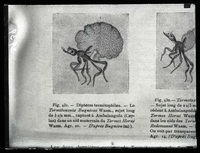

Termites? I couldn’t think of anything more uninteresting! Also, the images are not of actual termites, but are images of pages of books that have photographs and illustrations of termites printed on them. What?

Now insects are not entirely out of scope of a natural history image collection, but considering that the University’s Division of Entomology and Economic Zoology was organized administratively in the Department of Agriculture, and not in the College of Science, Literature, and the Arts (SLA) to which the Department of Animal Biology and the Zoological Museum belonged, I was perplexed. Though courses on insects were offered in SLA, they were given to fulfill one of several sequences in the general course of study in Animal Biology. These pictures of pages of termite pictures are actually the first instance of the appearance of insects that I have encountered while processing the natural history collections associated with the Exploring grant (with the exception of a few references to infested taxidermy).

Slightly annoyed that I was spending my morning with termites rather than amongst the water lilies on Lake Minnetonka, or observing the ornithological antics of Thomas Sadler Roberts , I switched my efforts over to reading through some museum correspondence to provide some context and get down to the bottom of this termite business. Why am I looking at pictures of pages from termite books? I found my answer with a letter addressed to Zoological Museum director, Thomas Sadler Roberts.

From C.R. Stauffer, professor in the Department of Geology and Mineralogy, December 22, 1920:

“Dear Dr. Roberts,

Since talking with you I have had occasion to write Dr. Osborn and find that I can get the necessary lantern slides for the popular Sunday afternoon talk on ancient vertebrates. If you still desire me to give this and can arrange it for later in the year I shall be glad to do it for you. At the time you were talking with me I was in doubt as to my ability to get suitable material.”

Professor Stauffer had me at “lantern slides,” “popular Sunday afternoon talk,” and “suitable material.” In 1921, Thomas Sadler Roberts instituted his first major public education and outreach initiative at the Museum: Sunday afternoon lectures. Each Sunday during the months of January, February, and March, Roberts opened the Museum to the general public for three hours. For each afternoon opening, Roberts scheduled a lecture to occur at 3:30pm. Roberts lectured on topics such as “Itasca State Park and Its Wild Life” and “Our Birds as Winter Tourists,” but he mainly relied on guest lecturers to provide the Sunday program. Roberts reached out to his colleagues at the University and throughout the state to present topics related to their corresponding fields. The lectures were almost always supplemented with lantern slides, motion pictures, or some other type of visual element. For example, Professor Stauffer did give a lecture the following year on Sunday, February 12, 1922. His talk was titled, “Ancient Land and Fresh Water Animals in North America.”

I was able to find when and what Stauffer presented because Roberts prepared and printed a brochure that listed the schedule, title, and presenter for the “Sunday Afternoon Lecture Course” for each of the ten years that the “Course” was held (the program discontinued in 1930). After I found Stauffer’s letter, I tracked down the set of lecture course brochures in the Bell collection, and sure enough, on February 21, 1926, Dwight E. Minnich, Associate Professor of Animal Biology presented, “The History and Habits of the Termites or White Ants.” The glass plate negatives of pictures of termite books were produced in order to create lantern slides to illustrate Minnich’s lecture.

I was able to find when and what Stauffer presented because Roberts prepared and printed a brochure that listed the schedule, title, and presenter for the “Sunday Afternoon Lecture Course” for each of the ten years that the “Course” was held (the program discontinued in 1930). After I found Stauffer’s letter, I tracked down the set of lecture course brochures in the Bell collection, and sure enough, on February 21, 1926, Dwight E. Minnich, Associate Professor of Animal Biology presented, “The History and Habits of the Termites or White Ants.” The glass plate negatives of pictures of termite books were produced in order to create lantern slides to illustrate Minnich’s lecture.

Termites turned out to be pretty interesting after all.

After the termites, I encountered several hundred additional images of pages of books with printed images and illustrations of varying subjects. Stay tuned for more pictures of book pages (after I go back and match the subject matter of the glass plate negative image to the appropriate lecture title)…