We previously shared the story of how the Minnesota Geological and Natural History Survey started. The Board of Regents, charged by the state legislature to implement the Survey, hired Newton Horace Winchell to lead field explorations and serve as the State Geologist in 1872. Winchell referred to his first season of surveying the state of Minnesota as a “retrospective” reconnaissance, and stated prior to beginning his work that due to time constraints and available funding, the reconnaissance “would have to be a hasty and incomplete one.”

Winchell predicted what could be accomplished in the first year given his “means at disposal” in a letter to University President William Watts Folwell, dated August 15, 1872: “You can see that very little can be done in that way in Minnesota, when the greater share of the only fund ($1,000) to be devoted to the survey is absorbed in paying salary of the one man employed…” He outlined to Folwell the potential preparations that he would attempt to make:

“… A condensation of the geology of the state, so far as at present known, bringing out their features which make a survey desirable and necessary, and sketch in general what it must be the aim of the survey to accomplish. There, with what running about I can do myself, and a little geological map, seem to be the only attainable ends this year.”

So, how did he do?

Winchell’s cautioned approach when he referred to the implementation of the Survey reads as an attempt to manage expectations for what could be accomplished in the first year. By downplaying the expected outcomes, whatever initial work was completed would likely be received as a significant contribution and an impetus upon which to make a plea for further funding and support of Survey work.

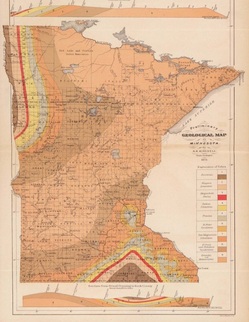

The First Annual Report of the Geological and Natural History Survey of Minnesota for the Year 1872 was submitted to the Board of Regents on December 31, 1872. The report followed along the lines that Winchell promised/predicted to Folwell. The State Geologist provided a “sketch in general” of the geology and natural history of the state in 131 pages. In addition to providing a concise overview of the history of explorations to the area of Minnesota beginning with Fathers Marquette and Hennepin in the 1600s, he included a bibliography of all published accounts of explorations of the state to date (1872). Chapter II included a statement of “general principles” inherent in the study of geology and related disciplines, and also included an overview of the general composition of the earth and a description of the formation of soils. In Chapters III and V he reported the “surface contour of the state,” and provided precise descriptions of the lakes and limestones of Minnesota. With the collaboration of Professor E.H. Twining, Winchell included Twining’s list of plants found in the vicinity of St. Anthony at the end of the report, followed by Winchell’s “little geological map.”

The First Annual Report of the Geological and Natural History Survey of Minnesota for the Year 1872 was submitted to the Board of Regents on December 31, 1872. The report followed along the lines that Winchell promised/predicted to Folwell. The State Geologist provided a “sketch in general” of the geology and natural history of the state in 131 pages. In addition to providing a concise overview of the history of explorations to the area of Minnesota beginning with Fathers Marquette and Hennepin in the 1600s, he included a bibliography of all published accounts of explorations of the state to date (1872). Chapter II included a statement of “general principles” inherent in the study of geology and related disciplines, and also included an overview of the general composition of the earth and a description of the formation of soils. In Chapters III and V he reported the “surface contour of the state,” and provided precise descriptions of the lakes and limestones of Minnesota. With the collaboration of Professor E.H. Twining, Winchell included Twining’s list of plants found in the vicinity of St. Anthony at the end of the report, followed by Winchell’s “little geological map.”

Winchell’s report also contained a list of “plans and recommendations” for the future progression of the Survey. First and foremost, the $1,000 budget allocated to the Survey was “too small.” He charged that the amount was insufficient to meet the dictates of the law that enacted the Survey and thus rendered the law “inoperative.” He further stated that $1,000 “does not command the respect and confidence of the citizens of the state and others, and serves as an excuse for refusing aid and co-operation. The survey should be independent of favors for which it now has to beg, sometimes to be scornfully rebuffed.” He added that additional services would have to be acquired, and costs incurred, in order to survey areas of the state that were not accessible by the railroads. Further, Winchell indicated the impact upon his personal compensation, “In order to conduct the survey on one thousand dollars per annum, the state geologist must find some other employment a portion of the year.”

How did the Board of Regents respond to the recommendations in Winchell’s report? The Meeting Minutes from April 1873 provide us with some insight…

At the April 2, 1873 meeting of the Regents, it was recorded that “Professor Winchell at the invitations of the Board made some remarks upon his desires in case he shall be continued in charge of the Geological Survey of the State.” For the following day, April 3, the Minutes state:

“Pres. Folwell made some remarks upon the matter of the State Geological Survey and his connection therewith. Prof. Winchell came before the Board and gave his views upon the best plan of conducting the Geological Survey. Gov. Austin moved that the Board do now establish the Chair of Geology in the University, and that the duty of giving instruction in the science of Zoology and Botany be assigned to such chair. The motion was adopted. On motion, the salary of the Prof. of Geology was fixed at $2000 per annum. Prof. Winchell was elected by ballot to the Chair of Geology.”

An entry in the Minutes from April 4, 1873:

“Prof. Winchell came before the Board and made a statement in reference to his salary as fixed on Saturday. On motion, the following was adopted: Resolved that Prof. Winchell receive in addition to his regular salary as professor, the sum of $400 for services on the Geological Survey during the Summer vacation, or such part thereof as may correspond with the time actually employed. ..”

When the Regents met again six days later on April 10, they further defined Winchell’s relationship to the University and extended his job description. The Minutes state the following:

“Duties and Offices: The following resolutions were presented: Resolved. That the following assignments of duties and office be made: 1. That the Professor of Geology be Curator of the Museum: adopted.”

Within a matter of months, the titles of Professor of Geology, Chair of Geology, and Curator of the Museum were added to Newton Horace Winchell’s resume, and the budget allocated for the State Geologist to perform the work of the Survey doubled. With added responsibility, greater authority, a higher budget, and a full season available to conduct fieldwork –a significant improvement to his “means at disposal“– how would the reconnaissance of the second year of the Geological and Natural History Survey of Minnesota be described? Hasty and incomplete, or concise and comprehensive?

Access The Second Annual Report for the year 1873 on the Digital Conservancy to find out.