Hunting and fishing were important to the daily lives of Minnesota’s early residents as a source of food and income. For the most part, pioneers could hunt and fish all they wanted as very little regulation existed that addressed “taking” in the first few decades of statehood.

According to the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR) hunting guidebook, “taking” is defined as “pursuing, shooting, killing, capturing, trapping, snaring, angling, spearing, or netting wild animals; or placing, setting drawing, or using a net, trap, or other device to take wild animals. Taking also includes attempting to take wild animals or assisting another person in taking wild animals.”

With no laws in place at the time that restricted the type or amount of animals, any early settler could capture and kill. Some of the state’s earliest residents ended up taking animals not only for survival, but also for sport, show, and science.

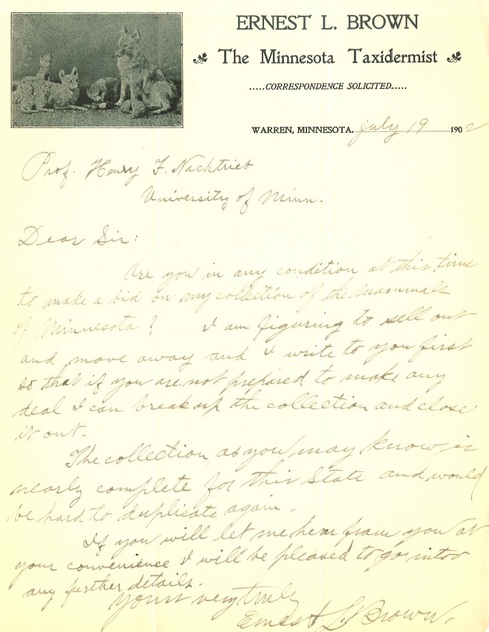

In a letter addressed to University of Minnesota Animal Biology professor and State Zoologist Henry Nachtrieb from September 12, 1891, we are introduced to Ernest M. Brown, taxidermist from the city of Warren in Marshall County, Minnesota:

Dear Sir:

As a naturalist and collector of Zoological specimens in this state I have often thought of corresponding with some one at the State University with reference to subjects of common interest. I may state here that I have been hunting and collecting in this locality part of the time for the last four years before that I was at Durand, Wisconsin where the bulk of my collections are stored. Of late I have been collecting mammals with careful measurements and data. Last winter was out with the Indians at the Lake of the Woods and secured the skin of the largest moose ever killed being seven feet standing height at shoulder. I also had the good fortune to kill two fine black bear one of which had cubs. I had figured on going across into Canada after Caribou the coming winter. Is the University supplied with full series of the deer which are natives of the State? The Elk are nearly extinct here. I secured two last winter.

I had wanted to ask you if there is any general law making provision for collecting specimens for scientific purposes. It seems to me there should be a provision of the law allowing the naturalist to complete his collection without violating the law.”

Though we don’t have a copy of Nachtrieb’s letter in response, Brown’s next letter suggests that Nachtrieb indicated to Brown that with his permission, animals could be taken for scientific collections in state institutions. Brown wrote to Nachtrieb on October 22, 1891, “Your letter gives me the information I have been seeking that in-where to go to get authority to collect specimens. If you can give me the authority I can collect good specimens of moose Caribou foxes and lynx such as you need.”

Judging from Brown’s letters, by 1891, four years after the first comprehensive act was passed by the state legislature that regulated hunting in Minnesota, there existed little understanding of the newly instituted restrictions. Chapter 142 of the 1887 General Laws outlined “An Act for the Better Preservation of Game.” The first several sections declared seasons for specific species of birds and mammals and laid out the penalties for taking animals outside of the authorized dates. Any person found in possession of a bird killed out of season “forfeits not less than ten (10) dollars nor more than fifty (50) dollars for each bird so killed.” The unauthorized taking of mammals incurred a larger fine, “not less than twenty-five (25) dollars no more than seventy-five (75) dollars for each animal so killed or destroyed.”

The 1887 Act also established the position of a game warden who was appointed by the governor to a four year term. The Act directed the appointed warden to enlist deputies to assist him to “faithfully enforce” the instituted laws related to the preservation of game in the state.

By 1889, harsher punishments were written into “An Act for the Preservation of Game.” Default of payment of the established fines resulted in “imprisonment in the county jail not less than ten (10) days nor more than sixty (60) days.“

In April of 1891, the state legislature established even stricter regulations on the taking of animals and also created The Board of Game and Fish Commissioners, a five member body appointed by the governor, to oversee the implementation of “An Act for the Preservation, Propagation and Protection of the Game and Fish of the State.”

The 1891 legislation did more than establish seasons, it prohibited hunting of certain species outright: “Provided, That no moose, caribou or reindeer shall be killed or sold or offered for sale in this state for five (5) years next after the passage of this act. Any person offending under this provision shall be guilty of a misdemeanor.”

It is likely that Brown was uninformed about the 1891 restriction on moose and caribou when he wrote Nachtrieb promising to secure specimens for the University with Nachtrieb’s permission. Nachtrieb must have replied to Brown to inform him of the new restrictions, as Brown’s next letter to Nachtrieb included some frank opinions about the changes in game legislation.

Ernest L. Brown, Warren, to Professor Henry Nachtrieb, State Zoologist, University of Minnesota, November 8, 1891:

“Dear Sir:

On my return from a ten days trip after deer I received yours of Oct 27. I had noticed the decision of the Game Commissioner, I presume that is the law and I believe in protecting the game, I consider it an unjust law however which entirely prohibits collecting specimens for strictly scientific purposes. I shall always believe that I have an “inherent right” to make a scientific collection. This may be treason, it is the way I feel.

I have a good collection of moose however and can, if necessary go across the boundary into Canada after Caribou. I have never made it a business to collect specimens to sell but have kept the most of my collection expecting to become connected with some scientific institution where they would be of use. I hope to get a place where I can do taxidermic work part of the time and part of the time collect in the field being thus enabled to study the subjects to advantage and do justice to the work in mounting specimens. “

Brown again wrote to Nachtrieb in 1893 and asked if there was a position within the University as a taxidermist to assist Nachtrieb in developing the University mammal and bird collections. The letter contains a description of Brown’s collection of mounted animals:

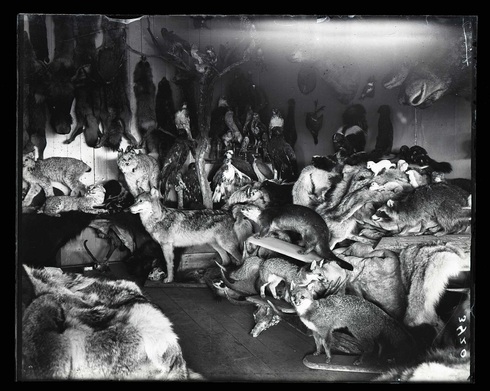

“My collection of the mammals of the State is undoubtedly the best in the State most of the specimens have been killed and measured by myself and are in an excellent state of preservation.

Have a very complete collection of material for Group of moose, have also the caribou, common deer, black bear and some of the smaller animals as foxes, skunks, etc.

Of material for groups partially completed I have female and young of elk, Buck and 2 fawns of male deer, two gray wolves, prairie wolf and young, badger and young, also fisher, marten, porcupine, loons, skunks, wood duck, squirrels, bats, moles, shrews, mice, also have a representative collection of m’ty [migratory] birds, bird skins, and eggs, and a collection of mound builders relics and skulls collected by me in the State.”

Brown offered to donate his collection to the University “were it possible to get assurance of a permanent place for myself with the institution.”

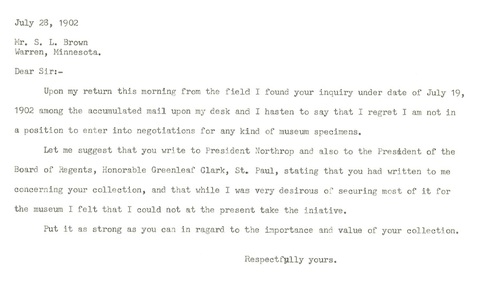

Ernest Brown was not hired as a taxidermist assistant at the University as there was barely enough funding afforded to support Nachtrieb’s salary as State Zoologist and Professor of Animal Biology let alone provide for a support position. Ernest Brown did not donate his vast collection of mounted animal specimens to the University, though he did contact Nachtrieb once more in July of 1902 with an offer to sell it. Nachtrieb replied, “I regret I am not in a position to enter into negotiations for any kind of museum specimens.”

– Letter from Ernest Brown to Henry Nachtrieb, July 19, 1902 (From the Henry Francis Nachtrieb papers, 1886-1929)

– Henry Nachtrieb to Ernest Brown, July 28, 1902 (From the Henry Francis Nechtrieb papers, 1886-1929)

The story of Ernest Brown, hunter, taxidermist, and collector of mounted animals, provides a brief snapshot into the conflicting interests and established norms present in the early stages of the conservation movement in America. Reading through Brown’s description of his collection, an exhaustive list of a multitude of animals native to Minnesota, one can only imagine how his accumulated mass of taxidermic animals may have appeared.

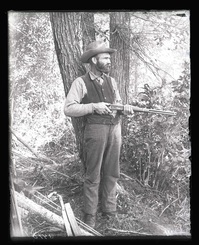

There is no need to imagine at the Exploring Minnesota’s Natural History project. Our extensive natural history collections document another interaction with Ernest Brown. Thomas Sadler Roberts, with camera in tow, visited Warren in Marshall County in the summer of 1900 to collect specimens of birds near Mud and Thief Lakes. Ernest Brown served as his field guide. Roberts captured Brown standing outside his “shop” and also captured the interiors of the “Ernest Brown Museum.”

The images show that Brown certainly “took” all that he could get.

– Ernest Brown in front of shop, Warren, June 1900