In Chapter 9 of his autobiography, My Life in Natural History, Walter J. Breckenridge shared his field experiences with Birds of Prey. In his role as taxidermist and exhibit preparator at the Museum of Natural History, Breckenridge was tasked with “collecting” specimens to mount for display in museum dioramas and small animal habitat groups. In June of 1928, Breckenridge traveled to Lake Superior in order to secure several specimens of Duck Hawk, also known as the Peregrine Falcon, for an intended museum display of an adult falcon and young at the nest.

In Chapter 9 of his autobiography, My Life in Natural History, Walter J. Breckenridge shared his field experiences with Birds of Prey. In his role as taxidermist and exhibit preparator at the Museum of Natural History, Breckenridge was tasked with “collecting” specimens to mount for display in museum dioramas and small animal habitat groups. In June of 1928, Breckenridge traveled to Lake Superior in order to secure several specimens of Duck Hawk, also known as the Peregrine Falcon, for an intended museum display of an adult falcon and young at the nest.

Breckenridge recalled –

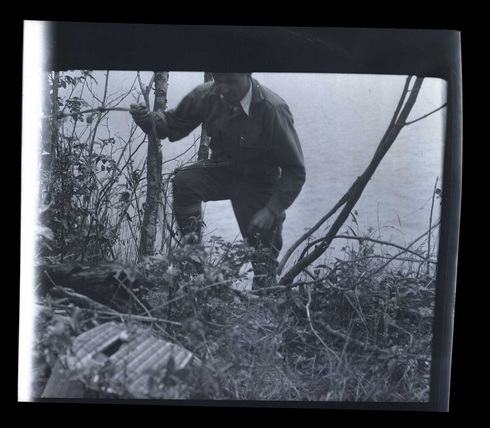

“In my early years at the Museum peregrine falcons were not common, but we knew that several pairs were present on the North Shore, and the taking of specimens was legal and justified, although I always hated to be asked to take them. We were anxious to have a small group showing this spectacular bird at a nest. In this case we decided that a nest with two young along the Superior North Shore would be sacrificed for this display. After shooting one adult bird I was lowered by rope to the precariously perched nest. There I made copious notes of these live birds…”

– Walter J. Breckenridge coming up from Duck Hawk ledge, north shore of Lake Superior, June 1928

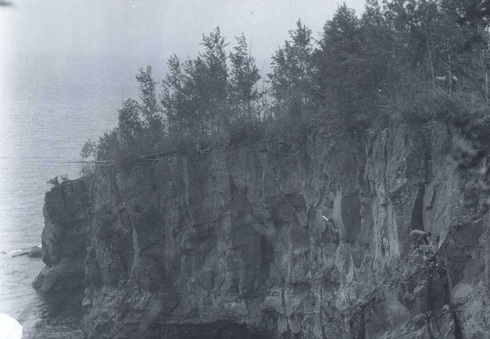

– Duck Hawk cliff, near Lutsen, Breckenridge on cliff, June 1928

– Duck Hawk, two young on ledge, north shore of Lake Superior, June 1928

– (l) Duck Hawk, two young, large, with mouths open

– (r) Duck Hawk, two young, large, mouths open

“…They were then dispatched, skinned carefully and salted, for return to the Museum for mounting. Here a most unfortunate thing happened. We had no deep -freeze unit in the Museum but we knew that the Anatomy Department of the Medical School had one just across the street, so we got permission to store these specimens in their freezer until I had time to mount them. When I went to get them they were gone! The Medical Department’s explanation was that an inexperienced assistant had been told to “clean out the freezer” and this he did with a vengeance, without any consideration for our name plainly written on the package. Thus the preparation of our group was interrupted. The adult bird was mounted, the photographic background was completed, and the foreground constructed. We definitely did not want to take any more peregrines, young or eggs from the wild. What to do? After some thought, I carefully measured some of the Museum’s egg collections and found that the white eggs of the marsh hawk were exactly the size of the peregrine’s. So I carefully colored a set of marsh hawk eggs, a much commoner species of hawk, and the group was completed, not as spectacularly as it might have been with two cute, fuzzy young falcons but with a set of beautiful rich brown eggs in their place. No one has ever questioned the real identity of the eggs although the Museum staff was informed.”