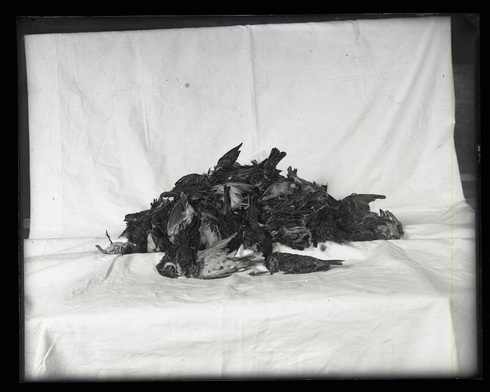

Upon first seeing the above image from the glass plate negatives in the Bell Museum collection, I was stunned. Dozens of dead birds stacked upon each other in a giant pile. The caption for this photograph reads, “Lapland Longspur, dead, 90 birds collected from ice on lake at Worthington, MN, March 22, 1904 (killed on the night of March 13, 1904).” My first thoughts: gruesome, grotesque, gross. It wasn’t until after I started to research the image, or try to find some discernible reason behind the impetus to capture a heaping pile of dead birds, that I learned of the tragic incident that lead to their death. I also learned a thing or two about environmental impact and bird migration.

The Lapland Longspur is a common medium-sized sparrow-like songbird that breeds in the Arctic tundra and “winters” throughout the continental United States and Canada. In the early spring of 1904 a large flock of Longspurs were caught in a winter storm in southern Minnesota and northern Iowa, resulting in the death of an estimated one million birds.

The incident is detailed in a paper written by Thomas Sadler Roberts that was published in The Auk, the official journal of the American Ornithologists’ Union, in Vol. 24, No. 4, October 1907 titled, “A Lapland Longspur Tragedy: Being an Account of a Great Destruction of These Birds During a Storm in Southwestern Minnesota and Northwestern Iowa in March, 1904.” In the article, Roberts credits the study of “unseasonable elemental disturbances” as well as “artificial obstructions of human devising” for bringing to light “a considerable amount of interesting and highly valuable information in regard to the always mysterious migratory movements of birds.”

In the middle of March 1904, several daily papers of cities in southern Minnesota carried notices of the destruction of large numbers of a type of small brown bird on the evening of March 13. A physician in Slayton, MN sent several of the dead birds to Roberts for identification. Roberts determined the birds to be Lapland Longspurs and as time passed learned that “abundant evidence of the bird destruction still remained” throughout the southwestern prairie of the state. Roberts sent his colleague Dr. Leslie O. Dart to Worthington and Slayton to investigate. These two locations were believed to have the greatest number of bird casualties.

Dr. Dart examined the number and distribution of the birds in these localities and conducted eye-witness interviews regarding what locals called “the great bird shower.” Roberts sent inquiries to officials in towns and villages throughout southern Minnesota and northern Iowa in order to better understand the circumstances of the wide-spread decimation of the Longspur population on that March evening.

Dart began his investigation in Worthington where birds were littered about the courthouse yard and along the streets. Roberts’s report indicated that on two small frozen lakes near the city, each with an area of approximately one square mile, “the dead birds were more conspicuous than among the grass and mud of the field and town, and the ice was found to be everywhere dotted with their bodies over the entire surface of both lakes.” Dart made an estimated count of the dead by measuring several standard sized areas on both lakes and counted the birds in each selected area. His averages estimated that there were over 370,000 dead birds on each lake.

– Dead Lapland Longspurs on a lake near Worthington, MN. From The Auk, published with the article.

Of the eyewitnesses interviewed, all indicated that on the evening of the incident, March 13, the temperature was around freezing, there was scarcely any wind, and the steady snowfall accumulated 5 or 6 inches by the following day. The birds were first witnessed in large numbers around 11:00 p.m. Roberts reported that a night watchman said that he “saw many fly against buildings… a great many were buried in the snow with just their heads out.“

While most eye-witnesses interviewed indicated that the birds “seemed to be everywhere,” consensus was derived that the dead birds “were most numerous under the electric lights and network of wires in the central portion of the village.”

Roberts described one of the more peculiar happenings of the incident in the article:

“A Mr. Drobeck reported that on the morning following the storm he noticed lumps or balls of snow on the roof of his barn and that when they thawed in the morning sun, they were found to contain live birds. The heads of the birds would first appear, and then, shaking off the snow, they would sit for a time in the sun drying and preening themselves and then fly off… Evidently the birds had become wet and snow-laden, and falling into the sticky snow had by their efforts rolled themselves into snow-balls.”

Worthington was not an anomaly. Similar stories were found in Slayton, Avoca, and Luverne in Minnesota, and Osceola County in Iowa. In all of these locations shopkeepers swept dozens of dead birds from the streets outside of their storefronts, and live confused birds lingered for days following the storm.

Roberts and Dart conducted detailed postmortem investigations of birds collected from the sites Dart visited. The birds piled on top of each other in front of a white background in the image from the glass plate negative were birds that Dart collected from the lakes in Worthington. These birds were dissected and “detailed autopsy notes” were made of their condition. Common injuries to the birds included skull fractures, cerebral hemorrhages, crushed bones, and ruptured internal organs. Roberts hypothesized that “in their utter confusion they must have dashed headlong onto the surface of the lake from a considerable height.”

By Roberts’s final estimation, “not far short of a million and a half birds were killed… All of the birds were Lapland Longspurs. Not an individual of any other species was found.”

Roberts concluded the article with a summary and explanation of the incident:

“As to the explanation of this catastrophe: It is plain enough that on the fateful night there was in progress an immense migratory movement of Lapland Longspurs leaving the prairies of Iowa where they had passed the winter months for their summer homes in the Northland, and that becoming confused in the storm-area by the darkness and heavy falling snow they were attracted by the lights of the towns and congregated in great numbers over and about these places. In their bewildered condition great numbers flew against obstacles and were killed or stunned while many others sank to the ground exhausted. It would also seem probably that a considerable number became wet and snow-laden by reason of the character of the snow, and thus, unable to fly, were forced downward to the earth to be dashed to death if falling from a considerable height, or simply stunned if from a lower elevation. This theory that the birds fell heavily or darted swiftly downward from high in the air would seem to be the only way to explain the presence and the extensively mutilated condition of the dead birds on the ice of the lakes at Worthington and elsewhere. Many of the dead birds found in the yard and field and on the roofs of buildings appear to have met death in the same manner.”

In reaction to one of the more gruesome images that we have encountered while digitizing the glass plate negatives from the Bell Museum collection, a colleague simply stated, “It’s not all pretty.”

Whether it is an image of beautifully speckled eggs that lay in a perfectly cylindrical nest highlighted by the glow of the morning sun, or 90 dead birds piled up on a white sheet, pretty or ugly, beauty or tragedy, we can still always learn something about our natural environment.