On page 676 of Vol. 19, No. 487 of the journal Science, a notice appears from Conway MacMillan, professor of Botany at the University of Minnesota, and State Botanist for the Minnesota Geological and Natural History Survey. The notice informed those within the scientific community that the 1904 party of attendees to the month-long field study at the Minnesota Seaside Station, would meet at the Hotel Dominion, Victoria, British Columbia “about the nineteenth of July.” The precise date was dependent on when their transport to the station, the vessel Queen City, was to set sail.

Just what was the chief botanist of the state of Minnesota doing in British Columbia, Canada? Another question: Minnesota Seaside Station? Minnesota isn’t beside any sea or ocean, in fact, it is nearly 2,000 miles away from the Pacific, and over 1,000 miles away from the Atlantic.

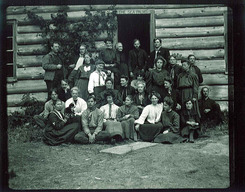

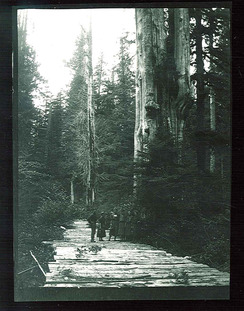

The station itself was actually a biological camp situated near Port Renfrew on the Strait of Juan de Fuca on the coast of British Columbia. It consisted of a two story log living house and two laboratory buildings that housed apparatus and materials used to conduct study in zoology and botany.

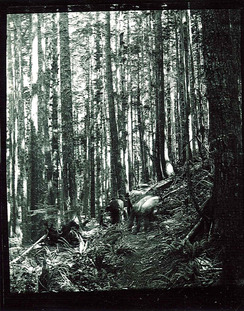

MacMillan advertised in Science that “The combination of sea and forest and the absence of any of the distractions of the town make this camp one of the best spots in the country for study, recreation and health, as the hundred teachers and students who have visited it during the last three years can very well attest.”

Just what did these hundred teachers and students do at the station, and how did this biological study center come to be? Additional notices MacMillan published in various scientific journals in each of the years that the station was in use provide description of daily activities, and images from the Department of Botany archival collection beautifully illustrate the scientific – and not so scientific – proceedings.

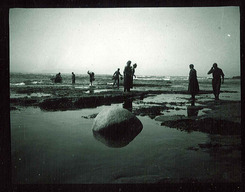

In the December 18, 1902 edition of Nature, MacMillan reported that the geography of the area where the station was based was composed of country rock with millstone grit and sandstone. Within pot holes that were worn by glacial boulders, tide pools formed that housed natural aquaria “each with characteristic distribution of plants and animals.”

Though they had ample equipment available in the laboratory building, the emphasis was on simplicity. MacMillan reported that there was no dredging apparatus, no pumps or conduits, and no electricity or gas. The station was “built and modestly equipped entirely though the cooperation of those who have enrolled themselves among its members.”

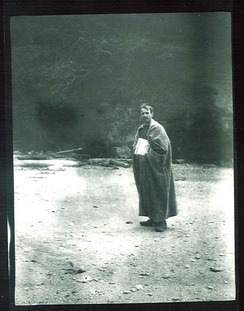

A key member was MacMillan’s colleague (and former student) Josephine Tilden, who despite being professionally based in a state nowhere near the ocean, pursued phycology (the study of algae) as her academic specialty. It was Tilden, who in 1898, traveled by canoe with a field guide and her 60 year old mother as chaperone, to the Straits of Fuca, where she located the site that would become the Minnesota Seaside Station.

It was through the personal effort and finances of Tilden, who purchased the land that the station was built upon, MacMillan and other University of Minnesota professors, and the $75 participation fee charged to participants (which included board, lodging, lab space, and instruction) that the station ran every summer from 1901 – 1907. Tilden lectured on algae, MacMillan conducted special courses on the ecology of kelps and the anatomy of liverworts. Guest lecturers, like Dr. Albert Schnieder, author of the leading textbook on lichens during the era, joined the party in the 1904 season to share his expertise.

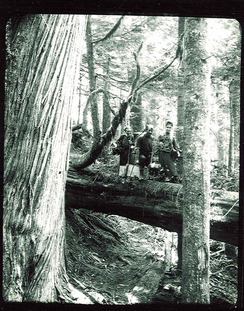

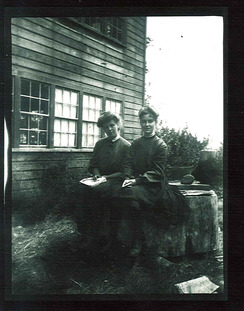

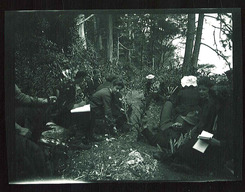

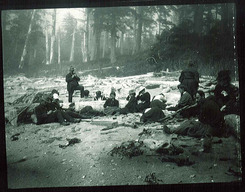

Click on the following images to see a larger version of students and scholars in action at the station:

It wasn’t all serious scientific inquiry, analysis, and classification at the station. The biologists formed a secret society, performed a “ho-dag” ritual, and generally lived life to the fullest in their serene and remote location. A report described station life:

“There is a freedom and unconventionality about the life at the Minnesota Seaside Station which has always proved very attractive to those who have taken part in it. An abundance of driftwood for campfires and bonfires is at hand and evenings spent with informal lectures on scientific subjects, round tables, song or story, or with mussel-bakes in the sea-caverns, are not soon forgotten.”

– Three of a kind, July 1901, Minnesota Seaside Station

– Tea party, July 1901, Minnesota Seaside Station

– Championship team of Victoria Island, July 1901, Minnesota Seaside Station

In addition to these photographs and the journal descriptions of activities at the station, the work done each summer was documented in the Postelsia, the station yearbook. The Postelsia (which is the name of a species of algae also known as a sea palm) contained a series of papers written by the scholars who participated in each season of station work. Thanks to the Google Book Project, you can access the Postelsia online. Original printed editions of the yearbook, along with the plates produced to print them, are housed at the University Archives in the Department of Botany Collection.

Despite the novelty of inspired inquiry by these scholar scientists, and the fact that the station activities were funded entirely by the participants at no cost to the University of Minnesota, the Board of Regents disapproved of the University’s association with the station. Frustrated over what he described as “political” dealings within the administration of the University, Professor MacMillan resigned in 1906. At the June 6, 1906 meeting of the Board of Regents, MacMillan’s resignation was read and accepted on the condition that he submit a final report on the Geological and Natural History Survey, for which he would receive a final payment of $600. At the May 2, 1907 meeting of the Regents, the body “Voted to instruct the Secretary to ask the members of the Department of Botany to return at once any apparatus, books or other property of the University that may have been taken to the Minnesota Seaside Station at Vancouver, B.C. , that no University property be taken to the Station hereafter; that the name of the University is not to be used on any advertising matter as there is no connection between the University and the Seaside Station.”

Dispute over the “final report” and payment of $600 between MacMillan and the University continued well beyond his resignation. In correspondence found between MacMillan and Fred Snyder, President of the Board of Regents in 1928, we learn, through MacMillan’s own words, of the demise of the Minnesota Seaside Station.

Conway MacMillan to Fred Snyder, February 2, 1928:

“Your predecessor, Mr. J.T. Wyman, who suffered from a pitiable inferiority complex, never clearly knew whether to listen to the political efficiency experts or to the University scientific experts. He therefore adopted a weak and vacillating policy of trying to carry water first on one shoulder, then on the other. The establishment of the Minnesota Seaside Station was a case in point. Realizing the necessity and desirability of having a marine outpost I laid before Pres. Northrop in 1901 a plan for the establishment of such an outpost, without any expense whatever to the University. He cordially approved of it, as did Mr. Wyman when it was brought to his attention. Consequently I organized a party of graduate students from Minnesota and other States and with their cooperative financial support built a laboratory camp at the most favorable spot known on the Straits of Fuca. I operated this camp successfully until 1906. In 1905, after the season on the Coast was over, I heard from Mr. Wyman, who held that I was probably knocking down a lot of money from the fees at the Seaside Station and it must be stopped. After this interesting conclusion on his part… I realized that the University of Minnesota did not provide an atmosphere in which I would hope to live happily and forthwith prepared to withdraw… The Minnesota Seaside Station subsequently fell in to ruins although, for another year, some of my students bravely tried to carry on. I have always regretted the loss to the Botanical Department of this outpost. Its research work was known and commended in every botanical capitol of the Americas, Europe, Asia, Africa and the Islands of the Sea. I created it without profit to myself or expense to the University and the political crowd strangled [it] in its infancy.”

Not the most pleasant of notes to end on, but a realistic one at the very least. The story of the Minnesota Seaside Station is a multi-faceted tale of good-spirited and purposed exploration in the undiscovered coasts of a foreign land not entirely understood by an educational administration and governing board back at home in land-locked Minnesota. The images and reports that survive to document this chapter of biological study at the University provide the occasion to appreciate the scenic seaside station as it once was. One report, that of the annual announcement for the Seaside Station in 1906, provides a better sentiment to end on:

“The magic of the mountains, the forest, the plains and the sea may enter your life and make all things have a new and deeper meaning.”

- • For further description of Josephine Tilden, who is considered to be the first female scientist at the University of Minnesota, her original trip to the Straits of Fuca, and her long and nuanced career at the University and in the field of phycology, see “Of Algae and Acrimony” by Tim Brady from the January-February 2008 edition of Minnesota, the quarterly publication of the University’s alumni association.