You may have read the title of this blog post and wondered, “What? I thought this was the Exploring Minnesota’s Natural History blog?” It still is. However, the title of this post addresses an unanticipated outcome of our project. By exploring Minnesota’s natural history, we have uncovered materials that help to document international cultural heritage.

Though a majority of the materials created by the Minnesota Geological and Natural History Survey relate to and are located within Minnesota, rich imagery and detailed descriptions were found that describe locations -and people- beyond our state boundaries.

This is where British Columbia comes in. We have shared multiple stories on the blog about the Minnesota Seaside Station near Port Renfrew along the Strait of Juan de Fuca in British Columbia. University botanist Josephine Tilden established the station in 1901. For six seasons Tilden and her colleagues from the Botany faculty at the University of Minnesota, and other scholars and students, studied the flora of the lush forests of British Columbia and collected and classified the kelp, lichen, and other sea life found on the beach in front of the Station, known today as Botanical Beach.

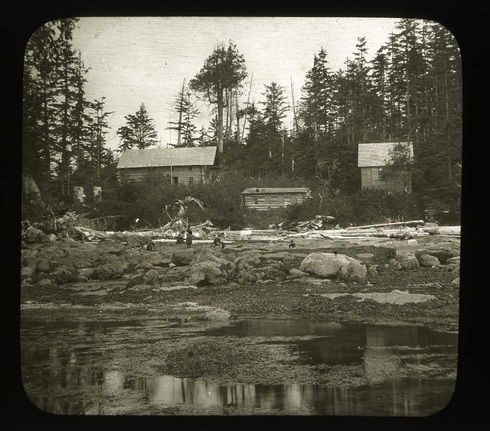

– Students and professors collecting sea life on the beach with the Minnesota Seaside Station buildings in the background, circa 1901-1906

To get to the Station, attendees would travel by rail across the country to Vancouver where a boat would transport them and their supplies and equipment to Port Renfrew, approximately three miles from the Station. Depending on the tides, a smaller boat would transport the travelers to the beach in front of the Station. If water travel proved too treacherous, attendees would walk to the Station from Port Renfrew on the trail cleared by the Canadian government. The approximate length of the walk: 2 hours.

To get to the Station, attendees would travel by rail across the country to Vancouver where a boat would transport them and their supplies and equipment to Port Renfrew, approximately three miles from the Station. Depending on the tides, a smaller boat would transport the travelers to the beach in front of the Station. If water travel proved too treacherous, attendees would walk to the Station from Port Renfrew on the trail cleared by the Canadian government. The approximate length of the walk: 2 hours.

Across the Strait from the Station was a village where the Pacheedaht resided. Seaside Station residents purchased salmon and handmade goods from the Pacheedaht. They visited their village and witnessed their traditions and customs.

How do we know this? Because the Department of Botany records contain the Ned L. Huff Lantern Slide Collection, which has two boxes of slides that illustrate life at the Minnesota Seaside Station. Huff, a University botany professor, created the slides from negatives that he produced while at the Station between 1901 and 1906. Huff happened to photograph interactions with the Pacheedaht while there.

We didn’t realize the importance of these images until we received an email from British Columbia. A woman representing the Pacheedaht Heritage Project, a project that seeks to document the cultural history of the Pacheedaht First Nation, was searching for information about Josephine Tilden, knowing of the history of the Station in the area of Port Renfrew . She came across the Exploring Minnesota’s Natural History blog posts about the Seaside Station and contacted me at the University Archives. As we were in the midst of digitizing Huff’s lantern slides, I quickly emailed back with the reference images that I had of the Pacheedaht and their village.

Over a week later, my co-worker came back in to my cubicle and asked, “Rebecca, are you expecting a phone call from British Columbia?” I paused, remembered my email, and questioned, “Maybe?”

The call was from several members of the Pacheedaht Heritage Project, who went on to reveal something that I was astonished to hear – the images from Huff’s lantern slides in the Department of Botany records, circa 1901-1906, are the earliest known photographic records of the Pacheedaht. The members of the Pacheedaht Heritage Project were kind enough to supply us with descriptions for the images, which helped us to better understand and appreciate their culture and traditions.

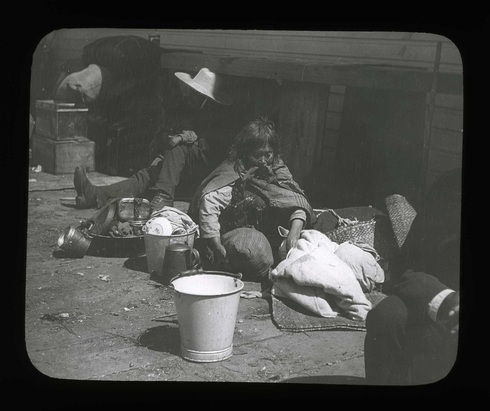

The images, along with the description Ned Huff provided in the catalogue to the lantern slides, followed by the background information supplied by the Pacheedaht Heritage Project:

PH Project, “This photograph, and the one below, were taken at or near the wharf in Port Alberni on Alberni Inlet on the west coast of Vancouver Island, a transportation hub at the time and apparently at the time of arrival of a coastal steamer.”

– “The Old Kloochman at Alberni”

PH Project, “Klootchman is the name for a native woman in the Chinook trade jargon”

– “Tribal house of the Indians at Port Renfrew”

PH Project, “This photograph has substantial historical significance for the Pacheedaht First Nation. We will need to investigate thoroughly, but the photograph was likely be taken in the Pacheedaht village at the mouth of the San Juan River in Port San Juan, and next to Port Renfrew. This large house was not occupied at the time of the photograph, likely during the summertime, as the house planks are not on the house. The architectural features of the house are significant.”

– “Indians gathering driftwood”

PH Project, “This photograph, and the next two, are apparently staged photographs, as it is unlikely that Mr. Huff would have been able to set up his glass plate camera for picture taking on a spontaneous basis.”

– “Loading the boat with driftwood”

PH Project, “Based on the background to this photograph, it and the previous two were taken at or near Botanical Beach near Seaside Station, as one can see the Strait of Juan de Fuca and part of the Olympic Mountains on the opposite shore.”

PH Project, “The same woman as shown in [earlier] photographs...”

Through my exchanges with the members of the Pacheedaht Heritage Project, I have witnessed first hand how the materials created as a result of the initiation of the Minnesota Geological and Natural History Survey – materials that I interact with on a daily basis – are vital documentation of the past. It is perhaps fitting that Exploring Minnesota’s Natural History is a project supported by the Legacy Amendment. Not only is the project helping the University Archives digitize their natural history collections, but it is also helping to document the legacy of a culture 1,800 miles away.

Now that’s what I call Minnesota Nice.